The jungles of West Papua are home to the Korowai tribe. I joined a gruelling expedition into the wilderness to meet them

In April 2015 joined an expedition into the southeastern jungles of West Papua, Indonesia.

I spent time with the Korowai, a tribe that traditionally lives in wooden houses high in the trees, and who didn’t have any contact with the outside world until the 1970s.

The Korowai are under threat. The Indonesian government is building villages to entice tribes to leave the jungle, so that their lands can be claimed for mining and palm oil plantations.

The Korowai’s traditional way of life could disappear in my lifetime. I didn’t want to miss my chance to meet them.

I first heard about the Korowai in Lonely Planet’s guide to Indonesia.

I lived in Singapore for nine months from 2014 to 2015 – and as Indonesia was on my doorstep, I spent time exploring Sulawesi, Java, Komodo and other incredible islands.

The Lonely Planet guide painted Papua as wild and untamed, so it captured my imagination.

It also claimed that visiting the Korowai was tough, and that travellers would spend “several days walking along muddy, slippery trails through hot, humid jungles, sleeping in tents, huts or tree houses to witness tribal life”.

But this daunting description didn’t put me off – it spurred me on.

As I crave road less travelled, visiting the Korowai sounded like the ultimate adventure.

When planning my trip to the jungle, I was fascinated to learn more about the Korowai.

As well as living in lofty treehouses and relying on the jungle to protect and nourish them, the tribe has a fearsome reputation and a history of cannibalism.

The practice was supposedly stamped out by Christian missionaries by the 1990s, yet stories of Korowai warriors eating rivals to kill evil spirts persist to this day.

But it wasn’t the Korowai I needed to worry about.

During the week-long expedition I had to deal with monster insects, perilous swamp crossings, days of drinking yellow jungle water, and getting horrifically sick in the depths of the wilderness – days from the nearest hospital.

As adventures go, it was pretty hardcore.

Welcome to the jungle: part 1

My journey to Korowai territory began in the Baliem Valley, in the central highlands of West Papua.

I spent an incredible week in the Baliem Valley – home of the Dani tribe – and had many adventures that will eventually feature in my blog.

I was joined by two doctors from Munich, Marián and Susanne, who soon became close friends.

I didn’t know it as I left the Baliem Valley, but in the wilds of Papua I’d come to rely on my companions’ medical skills.

Without them, I’d have been in a lot of trouble.

To get to Korowai territory we first had to fly from Wamena in the Baliem Valley – via the provincial capital, Jayapura – to Dekai, at the upper reaches of the Brazza River.

But, as is typical for Papua, even the flight was an adventure.

Although Wamena’s departure terminal has all the trappings of a modern airport – check-in desks, security barriers, baggage scales – it’s based in what looks like a corrugated iron cattle shed.

The airport has an open-door policy and anyone can wander in off the streets, including saggy old men wearing nothing but a Dani penis gourd who flog souvenirs to tourists.

The metal detector by the departure gate isn’t manned or switched on, and you can bring whatever you like onto the plane.

This was lucky for us as our expedition cook, Teron, was carrying hundreds of raw eggs in his hand luggage.

When we eventually made it onto the plane, there was no rest for my raw nerves.

Indonesian airlines often inherit old planes from mainstream operators, and boarding the Trigana flight felt like stepping back to the 1980s.

The seats were so worn that the padding was squashed flat, all white plastic fixtures were discoloured and cracked, and the safety instructions in the back of the seat in front had seen so much action that they were held together with sticky tape.

A few months after I returned from Papua, a Trigana flight on a similar route crashed in the jungle and everyone on board was killed.

Judging by the creaky state of the plane I took to Dekai, I feel lucky to have made it alive.

A day in Dekai

Having arrived late in Dekai – and with a long way to travel before nightfall – our priority was to get our surjat jalan travel permits verified by local police.

We sat for what seemed like hours in the stifling heat of the station, waiting for the chief who was in a nearby restaurant watching a boxing match.

The officers on duty were courteous and friendly, but seemed to ask our guide lots of questions about our group. They looked puzzled to see tourists in such a remote part of the country.

Eventually, the chief turned up. He looked about 17 and was dressed in a T-shirt and flip-flops.

He took a cursory look at our papers and waved us on. He just wanted to get back to the boxing.

After picking up last minute supplies – and as many cigarettes as we could carry, a mandatory gift for the Korowai – we went for our last meal that wasn’t cooked on an open fire.

Again, Papua offered an unexpected treat.

We had dinner in a place called Arbon – West Papua’s most flamboyant restaurant.

Unlike other wild and woolly eateries in Dekai, Arbon is impossibly clean and the chairs and tables are draped in outrageous green silks that would have made Liberace blush.

We were lucky to meet the brains behind the emerald decor – a young man who was delighted to see tourists so enamoured with his designs.

As for lunch, the local special – a creamy chicken and vegetable soup – was delicious.

It was also fun to relax and joke with my companions before the expedition set off.

After lunch we made our way to Dekai harbour, and loaded our supplies onto the longboat that would be our ride for the next few days.

News of foreigner visitors had spread, and locals lined the bank to take a look at the pasty travellers making their way into the jungle.

As I stepped into the boat, I was gripped by last minute nerves.

It suddenly hit me that I was travelling into the unknown, and heading for a place more remote than anywhere I’d ever visited before.

But as the outboard engine roared into life, I knew I was committed.

There was no turning back.

The journey begins

The trip to the tiny village of Patipi Dibawa set the scene for the next two days.

The longboat powered its way upstream along the peaceful Brazza River, heading towards Mabul – the last settlement on the fringes of the jungle.

On the first day the weather was glorious, and it was exciting to see stilt-house villages on the banks of the river, wave to locals in passing boats, and catch a glimpse of majestic hornbills as they flew overhead.

At the front of the boat sat a member of the Korowai tribe; a silent spotter who dutifully watched the river and waved to the captain if he spotted any hazards.

Crocodiles are common in the Brazza, and it was the spotter’s job to make sure we didn’t collide with one.

It would have brought our expedition to a nasty end.

Because we’d left Dekai later than expected, the final hours of our trip were in total darkness.

The captain didn’t spare the engine as night fell, and we continued to speed relentlessly into the blackness.

The only light was the glare from the spotter’s torch, who leaned over the edge of the boat to check the waters ahead.

Eventually, in the dead of night, we arrived at Patipi Dibawa. The whole village was asleep.

By torchlight we set up our tents inside the village schoolhouse and bedded down for the evening.

Outside we could hear rolls of thunder. Tomorrow, our guide said, the weather would not be so kind.

Waking up in Patipi Dibawa

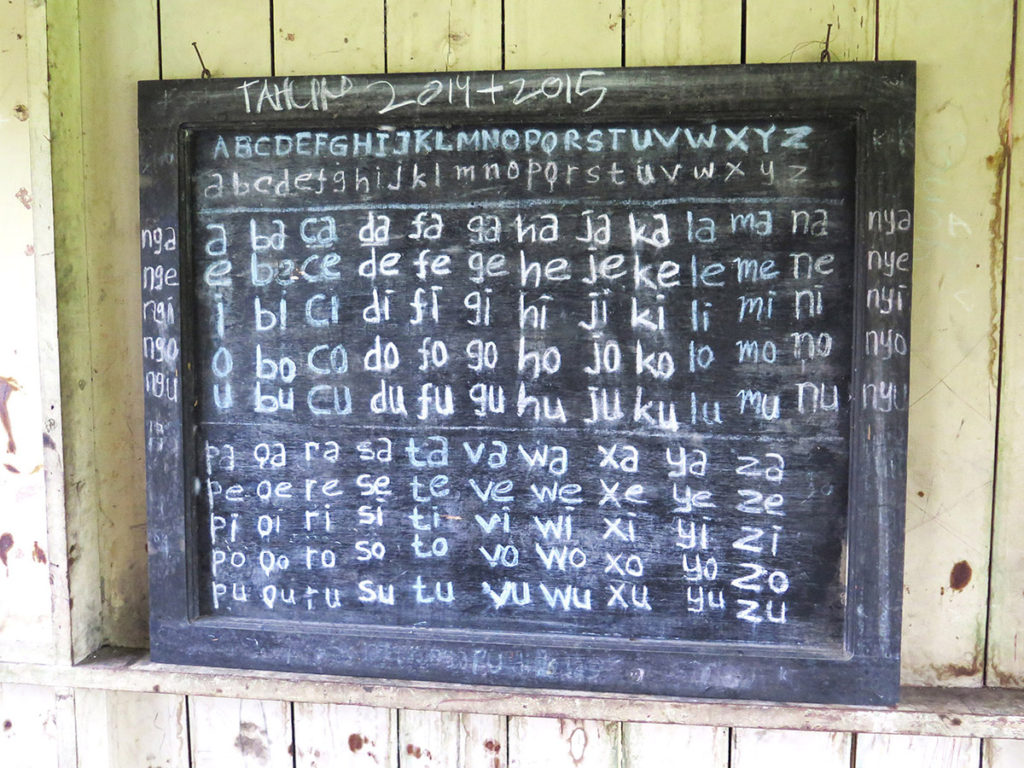

Check out these photos. Nothing unusual here, right?

But imagine arriving in the middle of nowhere in pitch darkness, and in the harsh beam of a flashlight glimpsing crude drawings of animals being abused by green-skinned demons.

Worse, having spent my youth absorbed in the weird fiction of HP Lovecraft, the strange combinations of letters on the blackboard seemed like something from a cultist’s spell book.

What the hell had we got ourselves into?

In daylight the blackboard made more sense. It was part of the Indonesian government’s strategy to provide education for remote communities who agree to leave the jungle.

By morning the posters were also less intimidating, and were clearly ham-fisted propaganda left by missionaries to encourage villagers to embrace Christianity and ditch their traditional beliefs.

I still had no idea who my hosts were, but at least they weren’t devil worshippers.

As we ate breakfast in the schoolhouse, we were surprised to see the villagers silently filing in and sitting opposite us.

They didn’t want food – we offered. They just wanted to watch.

Judging by the villagers’ pointing and giggles, we were obviously the butt of many jokes.

But their ribbing didn’t come across as cruel or sour. We felt welcome.

There was a delicious irony. We were travelling into the wilds to see ways of life that are rapidly disappearing, but ended up becoming the main attraction.

And we had to get used to this – it happened in every village we visited.

After breakfast we set off for the 8-hour voyage to Mabul, and our guide’s words from the night before rang true.

We were now travelling in torrential tropical rain. The previous day’s azure skies were swept aside by weeping granite, and we wrapped ourselves in waterproofs for the ass-numbing journey along the Brazza.

Around noon the rains subsided, just as we reached the mouth of the mighty Siret River.

Travelling upstream along the Siret is different to the Brazza; the current is stronger, there are wide sand banks to avoid, and fallen tree trunks often block the way.

It was no surprise that we saw fewer local boats the further along the Siret we travelled.

As we got further from Dekai, the condition of the stilt-houses on the riverbank sharply deteriorated.

Buildings made from solid planks were replaced by rickety longhouses pieced together from jungle wood. Where the walls had sprung a leak, the damage was repaired by blue plastic sheets.

For communities that reject government housing, keeping a roof over your head is a constant battle.

Eventually the captain pulled over at a sand bank for lunch.

The guide, spotter and cook got busy building a fire and chopping ingredients on a piece of cardboard on the riverbank.

Lunch was Spam and noodle soup. It tasted better than it sounds – but in the wilderness, beggars can’t be choosers.

Hello Mabul

Our journey along the Siret continued for another 5 or 6 hours. The weather improved, but the threat of storms hung heavily in the air.

As we got closer to our destination, we saw prospectors panning for gold by the side of the river, using traditional methods to search for precious metals.

The Papuan wilderness is rich in gold and minerals, but the Indonesian government and foreign investors have already staked a claim on the most lucrative sites.

The only way locals can grab a share is to illegally sift through the sand and rocks and hope for the best.

As dusk fell we caught sight of our final stop, Mabul.

Mabul is a small settlement of Korowai people, who were convinced by the Indonesian government to abandon their nomadic lifestyle and settle in permanent housing.

As the sky reddened there was no time to explore. We hauled our supplies to a house owned by the village chief, who’d offered to be our host for the night.

We set up our tents inside the wooden hut, then joined the chief and his family outside for dinner.

By moonlight we had our first taste of sago, a kind of flour made from the pulp of the sago palm.

Sago is the staple food of the Korowai, and can be eaten in various ways: rolled into balls, mixed with boiling water to make a glue-like paste, or made into a pancake.

Our hosts choose the latter option and generously shared their meal with us.

But while the sago pancakes tasted great – sweet, crunchy and nutty – I find it hard to imagine eating the same thing every day for the rest of my life.

After dinner, and with a tough journey ahead, our guide recommended an early night.

At first light we’d hire a small group of villagers as porters, and begin our long walk into the jungle.

The real adventure was about to begin. Find out what happened next in the second part of my story.